Salutations, Sleuths!

Welcome to the third post in our series on the tools you'll need to sleuth out misinformation in an environment that is positively saturated with it.

Our methods of detection are rooted in two paradigms developed by researchers to help people recognize misinformation quickly and easily.

One paradigm is Stanford's Civics Online Reasoning (COR), a framework built on three questions:

- Who's behind the information?

- What's the evidence?

- What do other sources say?

The second paradigm is Professor Mike Caulfield's four-part SIFT methodology, which stands for Stop, Investigate the source, Find trusted coverage, and Trace claims to their origin.

In Part One of this series, we used lateral reading to do a background check; i.e., vet information sources for possible biases before engaging deeply with the information. In Part Two, we assembled the clues; i.e., checked to make sure that any claim was backed up by reliable and relevant evidence.

At the end of Part Two, I mentioned that trying to verify every piece of information we see in an environment with boundless information is a huge undertaking—too overwhelming for any one individual. Thankfully, the internet also makes it easy to leverage the knowledge of experts, whether that means fact checkers, journalists, scientists, or other experts in a specific field.

Chase down tips

One thing I've learned throughout the process of practicing my use of COR and SIFT is that the boundaries between each element and the order in which you perform those elements isn't always linear. Back in Part Two, we looked at evaluating claims, including how the presence of an image can easily distract us from false information (see the case of Sugar the Anti-Work Horse, which I actually saw in the wild just this morning). We also talked about reverse-image searching, a nifty skill to have, and one that can lead to immediate debunking. For example, if you find that a photo purported to be taken during a natural disaster was actually taken years before, you know the photo is being used as misinformation.

But there's another important aspect when tracing evidence back to where it came from, and that's following links back to their original source. Personally, it seems to me that much of what I find searching for information or browsing recommended articles seems to be reporting on reporting—not the original article, interview, etc. If the author of this article isn't the person who verified the original claim, how do I know what's being said isn't being misinterpreted or being taken out of context? How do I know the original source is trustworthy? You have to follow links back, do lateral reading, etc. Watch Mike Caulfield (inventor of SIFT) do this in about ninety seconds here.

Take statements and see where they overlap

Once I was talking about my job at a doctor's appointment, and my doctor said something like, "With all the bad information out there on the internet how do you even know what's true anymore?" This was kind of alarming to hear, and not just because this doctor is someone I've trusted to perform outpatient surgery on me.

What is "true"? What is "the truth"? I don't know, I don't know if I ever can know, and the older I get the less comfortable I am with dealing in absolutes. But it feels self-defeating to give up on searching for the best information we can get because our understanding is incomplete. And I don't need to know the existential nature of truth when I'm trying to figure out an answer to an immediate question about a news item.

I haven't taken a science class in more than a decade, but I took a self-directed misinformation course from two science professors, Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West, who have since authored a book based on their course called Calling Bullsh*t. Their work has reminded me to apply lessons from the sciences to my own quest for trustworthy information, including that single findings rarely prove anything definitively. Instead, science works by process, helping us to build understanding of our world by developing consensus among experts.

One advantage to having access to so much information at our fingertips is that it's easy to get a good idea of what information is good by investigating other resources and seeing where multiple resources agree (after making sure you're reading a source making its own claim and not quoting someone else's). And to do that you'll need to learn who to rely on.

Don't trust just anyone

In each of these installments, I've mentioned that COR was developed in response to a study that showed professional fact-checkers out-performing college students and PhD-holding historians on verification. Lateral reading was one skill fact-checkers employed. Another was something called "click restraint," which means skimming your search engine results before clicking. Google (or your search engine of choice) is not objective, and the top result may not be the best one. View a two-minute video from COR here that explains the concept here.

Click restraint is far easier to practice once you have a handle on which resources you trust and those you don't. So how do you know?

Build a crack team of experts

Modern life does not seem to be built for patience or slow-moving activities. But building trust takes time. And when it comes to sniffing out misinformation, time you spend building up a collection of trusted sources can pay off in the long run as you learn to rely on others who have deep knowledge of things you may not know much about.

One useful habit to build when seeing what other sources say is to familiarize yourself with professional fact-checker websites. While news sources may skew towards the left or right of the political spectrum, fact checkers' jobs are to verify, not to persuade (although, of course, no resource is completely objective). We have a librarian-curated list here on our Spotting Misinformation page. As an added bonus: you can gain a little more expertise yourself by engaging with fact-checking resources and apply their debunking skills on your own.

As you consume information over time, you can develop reflexes to check trusted resources or information creators to see what they say about claims. But it's also a lifelong process of vetting, checking, and cross-checking information sources to see where they may either reinforce or refute each other. I tend to follow a lot of journalists and researchers on Twitter to see what they're publishing and how they're applying their expertise or intellect to situations that may not rise to articles, studies, etc. This can lead me to other good resources. SIFT creator Mike Caulfield shows what checking other sources can look like in this video.

How you select who to trust depends a lot on yourself: what topics are important for you to understand? What credentials would be important to you in building your collection of trusted resources? What makes you feel like you trust a resource? What cognitive biases may be contributing to your choosing to trust this resource? Is this resource committed to any sort of ethical framework or publishing standards (e.g., a mainstream news source that employs journalists trained in fact-checking)? What if this resource is the only one investigating a particular topic?

As an example: I found a resource I really like in a rather unexpected place, addressing an element of misinformation that's rarely investigated by professional fact-checkers. Like many people, I've seen a ton of videos on Facebook that show simple recipes or lifehacks from channels like Five-Minute Crafts or Tasty. Then I found Ann Reardon's How to Cook That YouTube channel. Reardon is an Australian food scientist and professional baker who has a whole series of videos debunking videos that don't give the desired result or could be downright dangerous.

I found myself wanting to trust Reardon because of her no-nonsense demeanor, her insight into how food works (of which I have very little) and what it's like to be an independent content creator on YouTube, and the lengths she goes to to be transparent when testing claims. But I had to check myself because I know I can be easily charmed and we're predisposed to trust videos. As I watched more, I was impressed to see her engage in lateral reading (which you can see in this long video, starting at about the 8:55 mark).

I realized that I needed to do a bit more vetting, especially because I know that YouTube isn't fact-checked and the platform and its creators make money by keeping viewers on YouTube. I looked at Wikipedia to find some information that seemed to confirm Reardon's background in food science. I also looked into the 5-Minute Crafts YouTube channel, whose work Reardon often debunks, and found an article from Vox that's a deep dive into 5-Minute Crafts' ascension on YouTube. I also dug up an article that both cites and confers with Reardon's work by a writer with a background in writing cookbooks, and even saw a technology reporter at the BBC recreate some of her experiments to similar results.

Running all that information down took quite a bit of time. But after all of that, I feel like my trust of Reardon is justified. Plus, I got to practice using my verification skills using the tools at my disposal. Overall, I think it was worth the time spent so that I can enjoy her videos without worrying about being led astray.

If you'd like to learn more about these and other skills to help you spot and stop misinformation, we have some upcoming virtual programs, which you can view here. In the meantime, start exploring resources to help you increase your anti-misinformation tools and skills on our new Spotting Misinformation page. And, as always, if you need to get in touch with a librarian on this or any other topic, just ask!

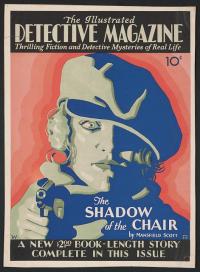

This image used for this blog post was found searching the Library of Congress Print & Photographs Online Catalog.