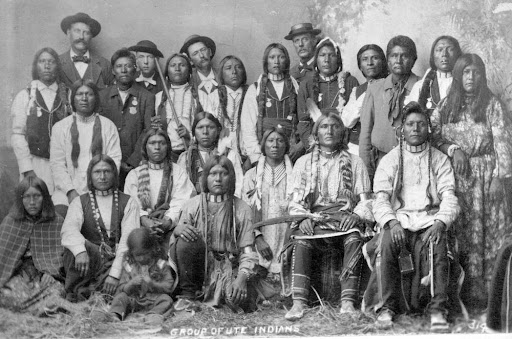

August 28, 1881: 1,458 Ute men, women and children of the White River Ute bands, escorted by cavalry, set out for a new reservation in Utah 350 miles away (the present day Uintah and Ouray Reservation). For more than five hundred years the Utes had lived and hunted in their traditional homes of the Colorado Rocky Mountains, known as the Shining Mountains. At one point their reservation lands covered almost all of what is now the Western Slope through well negotiated treaties. One man especially gained prominence: Ouray, who was created as ‘Chief of the Ute’ by the government, though some Ute did not recognize this and resented it. His wife, Chipita, was equally famous. Photo to the left of Ouray, William Henry Jackson Photo, Courtesy Western History Collection, 86.200.1063

The Northern Ute were forced to leave their lands following a lengthy negotiation. The Ute were among the last of the Native Americans to be removed and face the US army in battle. They had killed their hated agent, burned the agency and fought the US army to a standstill in 1879 in the White River War. It was just a little over a month following Sitting Bull’s surrender to the US army. The Northern Cheyenne were run to the ground after a failed bid to return home that year. Only Geronimo and the Apache would hold out longer.

The Utes in Colorado consisted of bands; in the north were the Grand Utes who lived along the Grand River (today the Colorado River), the Yampa Ute who lived along the Yampa river and the Uintah Utes whose range stretched across Utah. These bands were known as the Northern Utes.

To the south were the Mouache, the Capote and the Weeminuche of Southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. The final group of Utes lived in central Colorado, the Tabeguache or Uncompahgre. This central band was Ouray’s people. There was a brief war with the Southern Utes in 1854-55 in Colorado and New Mexico. Ouray refused to commit his bands to the war when asked. Otherwise the Ute maintained a peaceful relationship.

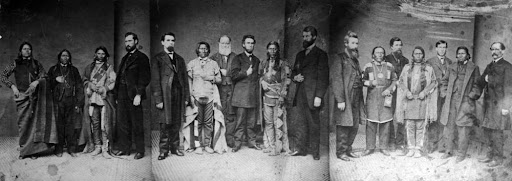

When John Evans became territorial governor of Colorado he was faced with mounting tensions with the Plains groups. When the Utes offered their friendship to the new governor Evans agreed. This led to a Ute delegation visiting the US Capitol in 1863. The delegation included Ouray, which started his reputation as a peace negotiator. While visiting he saw the extent of US power, leading Ouray to see the futility of armed conflict.

Following the visit Evans held a council with the Ute leaders at Conejos. The Utes ceded their hunting rights to lands east of the Continental Divide including Denver. In exchange for these land concessions the Utes were to keep their land west of the Continental Divide ‘forever’ along with annuities. It was one of the best treaties an Indian Nation had negotiated.

By 1868 prospectors were demanding more. Ouray and other important chiefs went back to Washington DC. It was here Ouray gave his most famous speech, including this statement: ‘The agreement an Indian makes to a United States treaty is like the agreement a buffalo makes with his hunter when pierced with arrows. All he can do is lie down and give in.”

The new Treaty of 1868, the Hunt Treaty, named after the Indian agent, redefined the borders of the Ute lands. The Uintah Utes were moved to Utah, and the Utes had to cede the Yampa River valley along with Middle and North Park, favorite hunting grounds, which had already been overrun by prospectors. The new northern border followed the northern line of modern Rio Blanco county. Again they were promised that the rest of the lands would be theirs.

But again it only lasted a few years. Gold, silver and other precious metals were found in the San Juans of central Colorado. Prospectors again penetrated into Ute lands despite the 1868 treaty.

Ouray could not understand why the United States could not control its people. Governor Edward McCook, in his biannual address to the Colorado Legislature, railed against the size of the Ute Reservation.

With the Utes remaining friendly, it would prove harder to move them; no war or massacre could be used as a pretext. Nonetheless the pressure to remove them was growing. Miners continued to invade Ute lands; when they were moved off by the army they just came back. The Utes held to their rights and fought off any attempts to negotiate another treaty, insisting that the US should honor the 1868 treaty.

Another council was called, this time attended by most of the Utes at the Los Pinos Agency, near Saguache. Governor McCook spoke first, explaining he was authorized to negotiate another treaty with them and he wanted it to be voluntary.

Ouray spoke for the rest when he stated, “We do not want to sell a foot of our land - that is the opinion of all.” Nothing came of this negotiation.

While the government was trying to negotiate with the Utes, the miners had united into an organization and threatened to use violence against the US army should they try to evict them again. The Territorial government gave in quickly, troops pulled out and the miners flooded into the San Juans in the summer of 1874. Another council was called for, this time at Fort Garland. Otto Mears, who had befriended Ouray and held a lucrative contract with the Indian Agency, provided the breakthrough with Ouray. Bribery. Mears suggested that Ouray be given a sum of a thousand dollars and could keep an important Hot Spring near his home. This broke the deadlock and the Brunot Treaty (named for the Indian commissioner) was signed September 1874.

The Ute gave up the San Juans in Central Colorado, leading to the towns of Durango, Silverton and Lake City. Because of this, Ouray earned resentment from several of the tribes, leading to assassination attempts. Nonetheless the Utes had managed to keep most of their lands, but it was clear that pressure would continue. (Part 1 of a 2 part series)

Blog post by Brian Johnson, Hampden Branch Library.